The human sense of touch, often overshadowed by vision and hearing, holds a profound yet understated role in our daily interactions. From the gentle brush of a loved one’s hand to the rough texture of a brick wall, tactile feedback shapes our understanding of the world in ways we rarely pause to consider. This intricate system of receptors and neural pathways doesn’t just relay physical sensations—it anchors us to reality, influences emotional states, and even alters cognitive processes. Yet, despite its ubiquity, the science and philosophy behind touch remain fertile ground for exploration.

At its core, touch is a dialogue between the external world and our internal perception. The skin, our largest organ, is studded with specialized receptors that detect pressure, vibration, temperature, and pain. These signals travel at lightning speed to the brain, where they’re woven into a coherent experience. But what makes touch uniquely compelling is its reciprocity. Unlike sight or sound, which feel unidirectional, touch often demands engagement: to feel is to be felt. This mutual exchange underpins everything from handshakes to the comforting weight of a blanket, creating a silent language of connection.

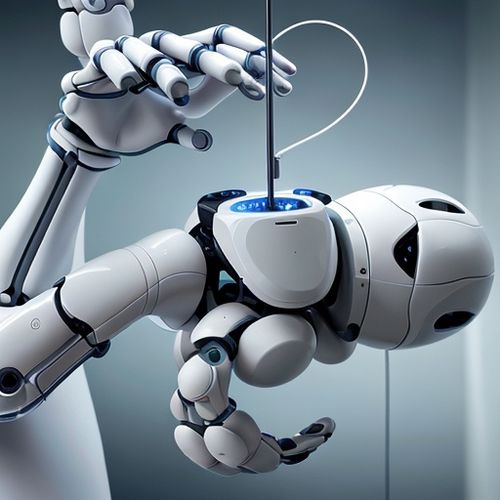

Modern technology has begun to harness this principle through haptic feedback, simulating tactile sensations in virtual environments. Smartphones vibrate to mimic button presses; gaming controllers shudder with on-screen explosions. Yet these engineered responses pale in comparison to the nuance of natural touch. A surgeon’s fingers discerning tissue density, a musician’s bow gliding across strings—these are feats no algorithm can fully replicate. The gap between artificial and organic touch reveals just how much we still have to learn about this primal sense.

The emotional dimension of touch further complicates its study. Psychologists have documented the “skin hunger” phenomenon—the distress caused by touch deprivation—while anthropologists trace how cultures codify touch differently. A pat on the back signifies encouragement in New York but might cause offense in Tokyo. Meanwhile, the rise of touchless interfaces during the COVID-19 pandemic created unintended consequences, from diminished trust in healthcare settings to the eerie sterility of once-bustling public spaces. These observations suggest that touch isn’t merely informational; it’s foundational to human bonding and societal cohesion.

Philosophically, touch challenges the mind-body divide more than any other sense. When we stub a toe, the pain feels simultaneously physical and mental, blurring Cartesian dualism. Ancient Greek skeptics even used touch as proof of reality’s elusiveness—press a single finger against your eye to see the world double, they’d say, revealing perception’s fragility. Contemporary researchers echo this by demonstrating how touch can be fooled (rubber hand illusion) or enhanced (sensory substitution devices), proving that our tactile map of reality is both malleable and deeply personal.

Looking ahead, breakthroughs in tactile technology promise to redefine human experience. Brain-computer interfaces may someday transmit touch across continents, while advanced prosthetics could restore nuanced sensation to amputees. Yet these innovations also raise ethical questions: Who controls tactile data? Can virtual touch fulfill emotional needs? As we stand on the brink of a haptic revolution, one truth becomes clear—the way we touch and are touched will continue to shape not just individual lives, but the fabric of society itself. The silent conversation of skin and surface, it seems, speaks volumes about what it means to be human.

By Joshua Howard/Apr 19, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Apr 19, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 19, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 19, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 19, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 19, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/Apr 19, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 19, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 19, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 19, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 19, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 19, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Apr 19, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 19, 2025